The Zambia Red Cross Society (ZRCS) has been assisting affected population in Zambia through the IFRC global Emergency Appeal for the COVID-19 pandemic. Among its response options, ZRCS has provided cash support to the affected households whose members had lost their income or were at risk of adopting negative coping mechanisms to meet urgent needs in the context of the global pandemic.

During the month of November 2020, ZRCS registered 1,303 households and carried out the verification and validation of those in Chililabombwe and Kalulushi districts. Each family received ZMW 410 per month for a period of 6 months. This assistance was provided in two instalments, with each instalment covering amounting ZMW 1,230 for 3 months. The first instalment was disbursed during November 2020 while second and last tranche took place during March 2021.

ZRCS is part of the National Cash Working Group (NCWG) chaired by the Ministry of Community Development and Social welfare. The NCWG includes different organisations implementing cash assistance in Zambia. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, the NCWG held numerous meetings to harmonise COVID-19 emergency cash response for all partners in the country, to avoid duplication of efforts and also to ensure the partners are supporting the social protection efforts of the Government. The Chililabombwe and Kalulushi districts in the Central Province were assigned to ZRCS as its area of implementation to distribute cash assistance.

The most vulnerable families already registered for government social cash transfers and have been prioritised. The ZRCS applied vulnerability criteria to select the most vulnerable among the registered population. Each selected household was expected to meet at least one of the vulnerable eligibility criteria, such as:

- Elderly with 65 years of age and above;

- Female headed household;

- Child headed household;

- Households with chronically ill member/s;

- Households with differently abled people.

To find out more watch a short video on the “Zambia Red Cross Emergency Cash Transfer Response” clicking here.

Author: Zambia Red Cross Society

In Zimbabwe, the “Resilience through Disaster Response management; Multipurpose Cash Preparedness and Comprehensive School Safety Project” has concluded in 2020, after running for two years in collaboration with Finnish Red Cross (FRC), European Commission Humanitarian Aid Office (ECHO), UN World Food Programme (WFP) and British Red Cross (BRC) – with the main implementation being led by Zimbabwe Red Cross Society (ZRCS).

The first project objective was to increase the capacity of ZRCS staff and volunteers to plan and implement cash and voucher assistance (CVA) programmes to run effectively. The information and tools to increase knowledge and skills of those involved in delivering CVA were based on the Cash in Emergencies Toolkit developed by the Movement, as well as inputs by WFP.

ZRCS is in the process of successfully mainstreaming CVA, as shown by the use of CVA in the 2020 contingency plans in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. Its integration has also been included into plans for 2021-2023, and into the Standard Operation Procedure which is currently being finalised to ensure the COVID-19 adaptations and the IFRC 2030 strategic plans are fully considered.

An overview of the crisis

Zimbabwe is affected by food insecurity across the majority of the country due to drought and flooding which have led to 5.5 million people (59%) of the rural population facing food insecurity. People have also experienced a worsening economic crisis. As part of efforts to address lack of foreign investment and lack of USD cash, the government has introduced a range of policies in recent years.

Despite these policies, inflation has continued unabated, with inflation rate growing exponentially in 2019, and reducing the purchasing power of households with already depleted food stocks.

How did ZRCS prepare to deliver CVA?

Continuing to learn about the use of CVA remains a focus of the work of ZRCS, whose staff and volunteers received training both online and in person. A finance and logistics workshop also took place with a key focus on Financial Service Providers (FSPs) with participants from different provinces and from the headquarter, coming from finance, logistics and admin backgrounds.

Cash Simulation Exercise – Nov 2020

The partnership with WFP allowed to extend training to include information management and the use of SCOPE; a beneficiary and transfer management platform that supports the WFP programme intervention cycle. This project has enabled a productive relation between ZRCS and WFP. The partnership was established and evolved into a strong collaboration with ZRCS as the implementing partner in the Lean Season Assistance operations in 2019/2020. Additionally, a number of joint activities and training have also strengthened the delivery capacity of ZRCS.

What were the lessons learned?

Distributing CVA has faced a wide range of challenges, including a change around currency across the country, together with the sudden creation of new rules on the use of mobile money. Due to this the team had to adapt the modality used to distribute cash assistance different times, moving from physical cash in envelops to mobile money to vouchers. The preferred modality sometimes varied also from region to region, and from one month to the next, giving staff and volunteers an opportunity to show their capacity to be versatile.

Having a good connection to the communities helped make these transitions easier. Through this process the ZRCS had a chance to reflect on the importance of cash and voucher assistance for the community, whose feedback was recorded in different ways.

Using cash transfers increases flexibility, dignity of beneficiaries and it gives them a choice to make […] as the communities have different priorities. Some people need money for medication, some need money for food, some for school fees, so having cash makes all these options possible. This is why at the ZRCS we are proud of using cash and voucher assistance.

ZRCS staff member, 2019

This process also led ZRCS to strengthen its commitment to community engagement and accountability (CEA) and to organise a joint learning event with the Kenya Red Cross Society as well as a CEA workshop.

Standard Operating Procedures Review – Oct 2020

To ensure the use of CEA was going to become an integral part of the work of the ZRCS, duties related to CEA have been added into job descriptions and training has been provided to volunteers. ZRCS has also recruited a CEA officer to ensure that staff continues to engage the community and to be accountable to them when implementing the programmes designed to reflect their preferences. In this way, CEA has emerged as a key element to ensure the best choices are made to achieve the desired objectives when distributing CVA.

Extract from the ICRC, Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog channel, for the original blog, to access a short podcast on this topic or to read comments to the original blog click here.

By: Pierrick Devidal

“Cash has been an exceptional vector of progress in humanitarian action, empowering people, protecting dignity, mitigating the negative secondary effects of in-kind assistance, improving accountability to affected populations, increasing participation in humanitarian and development responses, supporting local economies and, last but not least, boosting operational efficiency, which in turn saves some humanitarian cash. But what happens when cash goes digital, bringing with it the risks of exclusion, discrimination, or surveillance? In this post, ICRC Policy Advisor Pierrick Devidal opens an honest conversation as to whether and how humanitarians should continue using digital cash.

‘Cash’ is no longer a dirty word in the humanitarian sector. Over the last two decades, it has evolved – from a synonym for operational agility, to a relatively niche innovative humanitarian approach, and now to a global standard of good humanitarian assistance practice. People love it, humanitarians love it, and donors love it. It is reasonable to say that its weaknesses are largely compensated by the benefits it brings. Cash is a humanitarian no brainer.

And maybe that’s the problem.

Because cash is no longer cash. It is dematerialized and digitalized. It is all forms of digital payments including prepaid cards, electronic vouchers, and cryptocurrencies – and it has your name on it. Unlike real physical cash, digital payments are linked to identities and personal information. As a result, they can identify, they can exclude, and they can discriminate. Yet, falling in line with the global digital transformation, humanitarian programmes using cash transfers have turned, en masse, to digital solutions.

There are logical reasons to consider digital cash a good solution – if cash has been shown to enhance autonomy and resilience, and the world is going digital, why should people affected by conflict be denied access to something most of us use on a daily basis?

In parallel, the dark side of digital solutions is emerging and the over-enthusiastic and relatively naïve fascination bias for digital technologies is passé. The infodemic, massive cyber-attacks, data protection scandals and ‘surveillance capitalism’ are shining a light on the paradox of progress and the dark side of digital technologies, calling for a more sober approach. It seems that the humanitarian sector is also starting to realize that, maybe, digital solutions are not always a no brainer.

And maybe that is a good thing.

As recent articles have highlighted, there may be a case against digital cash. While the cashless cash trend is accelerating under the influence of economic actors, donors and the COVID-19 pandemic, critics are pointing to the increasing risks of ‘data colonialism’, ‘surveillance humanitarianism’, ‘techno-solutionism’, ‘data injustice’ or ‘digital exclusion’. What cash can do, digital cash can do in reverse. The critics raise uncomfortable but important questions for the humanitarian sector.

In short, it seems that humanitarians are finally taking a deep breath and a step back from the race to adjust to the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ and realizing that in contexts where violence and persecutions are widespread, we need to talk about digital solutions and cashless cash.

Cashless cash vs. principled humanitarian action

There are many entry points and angles to this conversation. Some of them more obvious than others. There are technical dimensions that are related to operational considerations, risk management or data protection questions. There are strategic dimensions that are related to questions of positioning, competition and relevance. And there are political and ethical dimensions. It is a multilayered humanitarian puzzle.

Digital payments may create significant interference with the fundamental humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence, commonly referred to as NIIHA. It is however not clear yet whether, and how much, these tensions are manageable.

Digital technologies, including digital payment mechanisms, are not neutral. They are aligned with the political objectives of those who create and promote them, including tech companies, banks and governments. In countries affected by armed conflict or other situations of violence, these actors are – to put it mildly – not always neutral. Being associated with them or their objectives can raise perception issues and put the neutrality of the humanitarian actors who use them into question (and ultimately, jeopardize their security).

Because digital payments are often carried out in partnership with financial service providers that have significant control over the parameters of digital payments, including flows of personal and sometimes sensitive data, the operational independence of the humanitarian organizations who use them can become compromised.

Those same financial service providers operate under different legal frameworks and have a different mandate (i.e. profit), so partnering with them may create tensions with the ability of humanitarian organizations to operate and deliver with impartiality – based on needs only – and not on needs and, for instance, States’ security considerations.

Finally, by replacing the human element by a digital interface, some are concerned that we are sacrificing some crucial components of humanity.

Cashless cash and ‘do no harm’

The ‘do no harm’ principle is sacrosanct in the humanitarian sector – or rather, humanitarian actors always try to do as little harm as possible, by mitigating the negative impact that their interventions and activities may bring for the affected populations they serve, and to the environments in which they operate. But with digital payments becoming the standard, there is a feeling that humanitarian organizations really have no choice but to adopt them.

That pressure trickles down. Even when we may be able to identify some of the risks attached to digital payments, and without necessarily having the solutions yet to mitigate those risks effectively, we offer digital payment solutions to affected populations, and we don’t always offer them an alternative, particularly given that some say we live in a post-consent world. Do recipients really have a choice? Are we not transferring risks and this lack of choice to them; or, if we collectively decide to stop using digital payments, are we taking away power and making a paternalizing choice for affected populations?

These are not easy questions, and there are even bigger ones. Is it realistic or ethical to pause digital payments in humanitarian programmes? Can we really afford the human and financial cost of forgoing proven lifesaving assistance or of reverting to in-kind, which can be less effective? Do we need more regulation, or a plan B?

These are existential questions, because they relate to trust in humanitarian action. And the new oil is not data; it is trust. We invite our fellow humanitarians, States, the private sector and, most importantly, affected people, to join us in the conversation.

Extract from the ICRC, Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog channel, for the original blog, to access a short podcast on this topic or to read comments to the original blog click here.

By: Pierrick Devidal

An updated version of the Household Economic Security (HES) guidelines has recently been launched by British Red Cross. To download this document, the analytical overview and the HES glossary click on the links below:

- Household Economic Security (HES) guidelines – step by step guidance

- HES Analytical Overview – providing a list of driving analytical questions for a HES assessment

- Key HES Terminology – providing an updated glossary to help unpack the 3 components of HES and related concepts

The guidelines and all its supporting documents, including tools for data collection, a HES report template and example reports in multiple languages can also be found on the IFRC Livelihoods Centre Website.

The HES guidelines are based on the Household Economy Analysis methodology and can now be applied to both rapid and slow onset emergencies, and also used to gather baseline information for livelihoods and resilience building interventions.

Breaking down Household Economic Security into 3 components (food security, basic needs and sustainable livelihoods) can help colleagues of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement navigate the humanitarian and development landscape as part of their operational reality and mandate. The guidelines may also be useful for other actors involved in food security, economic security and basic needs and livelihoods assessments.

Ömer Eddağavi and his family have been living on unstable income since arriving in Turkey six years ago after fleeing conflict in Syria.

Relying on seasonal work on farms, forced Eddağavi to borrow money from relatives and friends when there was no job to feed his family.

“It is so hard to be dependent on debts when you are responsible for a crowded family. Because you don’t know if you will be able to borrow money next time,” said Eddağavi.

However, since the day they started to receive the monthly cash assistance offered by the IFRC and the Turkish Red Crescent, with funding from the European Union, Eddağavi and his family broke the vicious cycle of debt to stay afloat.

“Thanks to god, we can live without being in debt and pay our bills,” said Eddağavi.

More about the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN)

Funded by the European Union’s Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), IFRC and Turkish Red Crescent are providing monthly cash assistance via debit cards to the most vulnerable refugees in Turkey under the ESSN programme. This is the largest humanitarian programme in the history of the EU and the largest programme ever implemented by the IFRC.

ESSN is providing cash to the most vulnerable refugee families living in Turkey. Every month, they receive 120 Turkish Lira (18 euros), enabling them to decide for themselves how to cover essential needs like rent, transport, bills, food, and medicine.

*This story was originally published on Turkish Red Crescent’s kizilaykart.org website and adapted by the IFRC.

This article covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

The Cash Hub and IFRC have created a short tip sheet of abstracts and summarises from the IFRC (2020) Step-by-Step Guide for Rental Assistance to People Affected by Crisis and it intended to introduce the reader to some of the key concepts related to Rental Assistance Programming. To download the tip sheet please click here.

Rental assistance is an important programming option that has relevance to support people in crisis to access safe and appropriate shelter in a range of contexts. Many Red Cross Red Crescent National Societies and other humanitarian agencies are increasingly interested in this programming option. In 2020 IFRC developed the Step-by-Step Guide for Rental Assistance to People Affected by Crisis which can be accessed here.

A rental assistance programme often involves the provision of rental payments, but rental assistance goes beyond the provision of cash and voucher assistance. The objective of rental assistance is to ensure people’s protection and dignity, whilst enabling access to adequate accommodation for an agreed period of time, to make it possible for people to live in a dignified space without fearing eviction or abuse. An exit strategy must be planned from the outset, ensuring people can maintain their living conditions once support ends.

(Click here to read the original article hosted on the Türk Kızılay website)

The #powertobe campaign telling the stories of four refugees who receive cash assistance from Türk Kızılay Kızılaykart Cash Based Assistance Programmes has made a big splash on digital platforms. The campaign which brings the four refugees; Amal, Bilal, Davud and Hamad together with popular influencers such as İdil Yazar and Hamit Altıntop aims to become the voice of millions of refugees. We had a conversation with Orhan Hacımehmet, Program Coordinator of Türk Kızılay Kızılaykart Cash Based Assistance Programmes, about the details of Emergency Social Safety Net, the biggest cash based humanitarian assistance programme in the world.

How long has it been since the beginning of ESSN? What is the scope of the program? Where does the funding come from?

The introduction of the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) program dates back to 2016, following an initial pilot project in October 2016 and a national deployment started in November 2016.

The ESSN is the largest humanitarian cash-based assistance program in the world assisting more than 1.8 million vulnerable refugees living in Turkey. Each person in the family receives 120 Turkish Lira a month through a card branded as “Kizilaykart”, a debit card hosted by Turkish Red Crescent. In addition to regular assistance, we provide additional support for large families and family members who have a severe disability. The cash assistance helps families pay for food, rent, bills, medication, among other items.

The program has been running with funding from Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), and in partnership with the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Services, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and Turkish Red Crescent by the support of the Directorate General of Population and Citizenship Affairs (DGPC) and Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM).

Virtually half of the refugees living in Turkey are benefiting from the financial aid. What are the eligibility criteria? Is it only for Syrians? Is there an application process?

We focus on supporting the most vulnerable households with a focus on single-parent households, the elderly, the disabled, large families, and other vulnerable groups.

The programme aims to support not just Syrians but all foreigners living in Turkey under temporary protection / international protection / humanitarian residence permit which includes Iraqi, Iranian, Afghan, among others.

Individuals who would like to apply to the program should receive their identity cards from DGMM, make their address registration into MERNIS system (address database) from civil registry offices, get their disability health board report from authorized state hospital (in case of disability) and obtain and filling in the SASF / Türk Kızılay Service Centers forms required for the application. The application result is shared via SMS to individuals completing these steps.

Can you tell me about the concrete changes you observed in lives of the beneficiaries of the aid?

We are helping to provide regular and predictable cash assistance through debit cards so people can cover what they most critically need. We see the impact this has on their lives every day. Cash assistance gives people the freedom to pay for what they need most. We see that our help allows refugees to prioritize their needs with dignity and a sense of normality that has been lacking in their lives. Parents are able to keep a roof over their children’s heads and ensure they have enough to feed their families; medicine can be given to those that require extra care and people can stay warm through these cold winter months.

According to Nationwide surveys that have been conducted from the very beginning of the programme, we see that people are able to cover their basic needs in a dignified way without applying negative coping strategies. Managing debt, consuming diverse food and sustainable access to utilities with regular payments are some major indicators which have a positive effect in their life. The ESSN assistance has become a lifeline for the refugees even during the pandemic, which has made people more vulnerable, including their loss of livelihood activities.

Let’s move on to #powertobe… What do you aim for with this digital campaign? What are you doing to reach these goals?

The #powertobe campaign is intended to connect us all to what drives us and keeps us going. This has been a difficult year for all of us and the passions like cooking, sports or music are things that unite us. The campaign showcases four inspiring people who were forced to flee their country for Turkey who receive support from the Turkish Red Crescent and IFRC through the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN).

Davud, Amal, Bilal ve Hamad… Milyonlarca mülteci arasından bu dörtlüyü nasıl seçtiniz? Öne çıkan özellikleri nelerdi?

We sent out a request to refugees across Turkey we support through ESSN and asked who might be interested in sharing their story and their passion with the world. We received hundreds of people willing to tell their story, which we hope to continue showcasing in the future. These four had a powerful story to tell and inspired us with their passions.

Former football player Hamit Altıntop and YouTuber Chef İdil Yazar are the ambassadors of #powertobe from Turkey. Why did you choose them?

We collaborated with people who not only demonstrated a similar passion as the Syrian creators in cooking, parkour, singing or football but also shared the same value and stance as we do when it comes to refugees. İdil and Hamit understand the challenges refugees experience and recognize the critical support needed for refugees to take control of their lives.

Are you planning to extend the campaign? What are the next steps for #powertobe?

The campaign runs in Turkey, Austria, France, Spain and Romania until 5 January. We hope to continue sharing stories like Amal, Bilal, Davud and Hamad who inspire many and provide a voice for many more refugees who are recovering and rebuilding their lives in Turkey. As we enter the tenth year anniversary of the Syrian war with no end in sight, we know that the humanitarian needs will continue. We have seen the power of what cash assistance can do in helping families pay for the things they need most in difficult times – Turkish Red Crescent has been supporting refugees from the beginning and are committed to support refugees and other vulnerable communities for as long as there is a humanitarian need.

News Source: Hürriyet, 06.01.2021

Said loves reading and transforming his personal struggles into stories and poems. Each tells a different story close to his heart about love, loss and the everyday challenges of those forced to flee conflict, like himself.

“How can I be indifferent to the suffering of those people injured by bombardments,” he says.

“I write about humanity and homelessness. About the ones who were displaced just like us. I feel them and I feel their suffering. These are the people of my country – they are my family.”

Said is a 66-year-old Syrian refugee living in Turkey; he and his family were forced to flee their hometown in Syria’s southwestern area of East Ghouta in 2018.

Said remembers a beautiful life before the war, full of nature and books. Working as a farmer since he was 12, he was growing vegetables and raising livestock. Inside his house, he had a large library, filled with precious manuscripts and books from well-known philosophers.

When a rocket landed on their home in Eastern Ghouta, the whole library was engulfed in flames.

“The fire devoured everything, blew up everything. With all the past, with all the books it had, with all the documents there. It was my legacy and the legacy of my ancestors. And all were gone,” remembers Said.

When the rocket attack tore through his home, he remained under the rubbles with his three-months-old grandchild Jana and shrapnel from the rocket severely injured him and paralyzed almost one side of his body. With barely any time to recover, they were forced out of their village and crossed into Turkey.

Said’s wounds are still fresh. However, writing, reading and time with his little grandchildren help him hold on to hopes of a new life.

“I sit with my grandchildren, they are always with me. We play games together and I tell them stories. I think I am child-like to them,” Said says with a smile.

Starting over in a foreign country with a physical disability was not easy. Now, Said receives small cash assistance each month from the Turkish Red Crescent and IFRC, with funding from the European Union. Due to many health problems he and his family have, they use most of the cash assistance to buy medicine.

Funded by the European Union and its Member States under the Facility for Refugees in Turkey, the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) provides monthly cash assistance via debit cards to nearly 1.8 million of the most vulnerable refugees in Turkey. The cash assistance enables them to decide for themselves how to cover essential needs like rent, transport, bills, food, and medicine.

This article covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

- Written by: Sayanti Sengupta

- Organisation: Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre

- Role: Consultant, Social Protection

The 192 National Societies of the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement have been providing first-line emergency response services during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, many of which have included support to national governments in expanding their social protection schemes. The unprecedented health and economic impacts resulting from this pandemic have accelerated linkages between National Societies and governments, with stronger collaborations to adapt and expand coverage of cash and social protection interventions.

The ability of National Societies to be part of response actions during the Covid-19 emergency highlights their role in delivering assistance during future climate emergencies. As climate risks and vulnerabilities rise these contribute to increased loss of livelihoods, impoverishment, food insecurity and inflated migration flows. With trends indicating that climate extremes are intensifying, it is crucial to consider climate risks as threats that will require well-designed, nationally managed, sustainable instruments for dealing with emergencies. Linking humanitarian action with social protection efforts might provide an opportunity to reach those more at risk from climate change and increase the effectiveness of humanitarian response with long-lasting impacts. Delivering cash to vulnerable households in a timely manner can help prevent negative coping strategies and boost the resilience of people affected by crisis.

Some of these links were essentially captured in the session on ‘Strengthening Linkages with Social Protection: RCRC experiences and way forward’ which brought together National Societies using social protection to reduce vulnerabilities arising from climate risks. The session, hosted by the Technical Working Group on Cash and Social Protection in September 2020, as part of the Climate: Red Virtual Summit organized by the International Red Cross Red Crescent Movement, included an engaging panel discussion on how the Malawi Red Cross Society, Kenya Red Cross Society, the Pakistan Red Crescent Society and the Philippines Red Cross have been contributing to building up the responsiveness of national social protection systems for climate preparedness.

Experiences of National Societies in linking Humanitarian efforts with Social Protection for Covid-19 and beyond

During Covid-19, the Philippine Red Cross (PRC) has made use of pre-existing beneficiary lists of the national social protection scheme- the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), which is primarily used for poverty eradication but also has a shock responsive component to cover beneficiaries in the aftermath of typhoons. The lists, derived from the local governments, were used to target people who are generally excluded from the programme but require assistance due to hardships caused by the pandemic. For this reason, PRC extended coverage to those households which are not traditionally covered by the social protection system but were at risk during the emergency.

The Kenya Red Cross Society (KRCS) assists the national government in scaling up the Hunger Safety Net Program (HSNP), by supporting early action that uses automatic triggers for droughts. In general, KRCS supports in addressing climate vulnerability to droughts by horizontally expanding cash assistance to distribute cash to people who are not covered by the HSNP, and by increasing top-up amounts to people who receive cash assistance from HSNP. During Covid-19, KRCS has helped the government by sharing data and registering new beneficiaries to receive cash transfers.

The Malawi Red Cross Society (MRCS) has facilitated the use of social protection for floods and droughts in Malawi by providing support in identification, registration, and verification of beneficiaries for the National Social Support Programme. Especially for women who are particularly vulnerable to climate shocks, MRCS has implemented a crisis modifier using forecasts for horizontal and vertical expansions of cash transfers, in order to mitigate negative impacts.

The session thus captured the experiences of how some National Societies are working with social protection and primarily cash assistance. The need for National societies to respond to climate related disasters and coordinate with national social protection systems will only increase in the foreseeable future, and important learnings from these experiences were highlighted.

Key insights on using Social Protection for Climate Emergencies by National Societies included

- Success of effective humanitarian response of National Societies (NSs) to climate related shocks will depend on the strength and maturity of pre-existing social protection systems.

- Cash preparedness of NSs, which is often determined by availability of funds, established transfer channels, accessible distribution points and engaged community actors, is important to complement government schemes and extend support rapidly during climate emergencies.

- While social protection can go beyond cash and voucher assistance, cash transfers remain a tried and tested mechanism that is often favoured by governments and can be delivered rapidly and on scale.

- NSs can strengthen existing social protection (SP) systems by supporting the review of SP policy, the harmonisation of beneficiary registration, delivery of benefits, monitoring and evaluation, among others.

- Along with social assistance, NSs could consider complementarities with other parts of social protection (including labour-related interventions, job training, social service and care)

Philippine Red Cross

As one of the panellists in the discussion mentioned, “climate change is exacerbating risks that affect the most vulnerable, and in future it might become the main driver of such risks. Linking social protection and humanitarian action will be crucial to address such risks“.

Through initiatives such as the Technical Working Group on Cash and Social Protection and others, the International Red Cross Red Crescent Movement is increasing its preparedness and capacity to support such linkages around the world, helping to address climate risks and strengthening national SP programs.

By Lotte Ruppert

COVID-19 does not discriminate, but the pandemic has disproportionately impacted certain vulnerable communities. Migrants and refugees face particularly large risks, due to language barriers, limited access to public services and a larger reliance on informal labour. Each has diverse perceptions, fears and opinions that we, as a humanitarian community, must address if we want to see this pandemic end.

For Turkey, a country that hosts the largest refugee population in the world (over 4 million from places like Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran), this presents a unique challenge. How do you engage people with diverse languages, cultures and communication preferences, all while adhering to strict movement restrictions to curb the pandemic?

Despite the impressive efforts from governmental and humanitarian actors, our impact assessment from April 2020 showed that almost one-quarter (23 per cent) of refugee households did not feel like they were receiving enough reliable information about COVID-19.

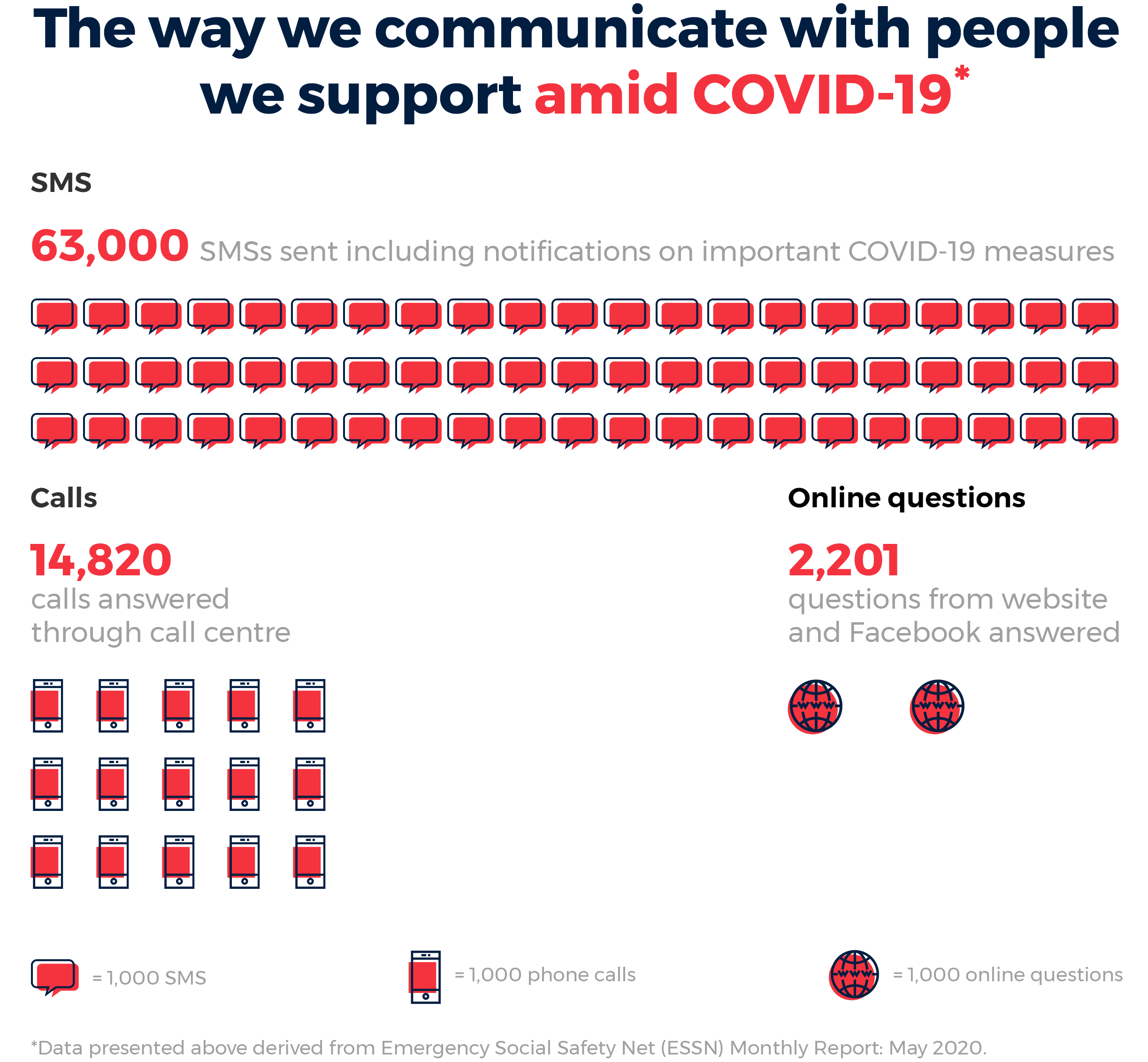

In response, Turkish Red Crescent and IFRC have ramped up their efforts to listen and engage with refugees in Turkey during the COVID-19 outbreak. Here are three lessons we learned about how to engage with communities at a large scale through the EU-funded Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN), the largest cash programme globally.

Lesson 1: Use a wide variety of communication channels

Everyone communicates differently. In ESSN, we rely on a range of different channels to allow people to speak with us in a way that they prefer and trust, including Facebook, regular SMSs and our toll-free Call Centre, where all operators have been trained to respond to COVID-19 related concerns and to provide hygiene advice or updates related to ESSN.

But these remote communication channels are not enough.

Refugees in Turkey have expressed their preference to share more sensitive concerns and complaints during private face-to-face conversations. Our nine Service Centres, spread across Turkey, have remained fully operational in order to provide information and support to people during the COVID-19 outbreak, with robust measures to ensure the safety of both its staff and visitors. This approach has been crucial to building trust.

Lesson 2: Do not ignore rumours

“I have an ESSN card but I saw on Facebook that my monthly cash assistance will soon be ended. What is the reason for that?” asked a refugee recently via our call centre.

This “fear rumour” reflects the anxieties of refugees living in Turkey that ESSN may end.

Another refugee family shared: “We are currently receiving ESSN cash assistance, but we have seen on YouTube that Turkish Red Crescent will now also give us rent assistance due to the impact of COVID-19”.

This is a clear “wish rumour”, reflecting the hope of refugees for more support during these difficult times.

The spread of such misinformation and rumours has always been a challenge for ESSN. But we learned that during the COVID-19 pandemic – a time of increased insecurity and stress – it is even more important for us to monitor the appearance and spread of misinformation.

The best defence is to prevent rumours before they start. We share regular information updates, getting accurate, trusted information into people’s hands before rumours have a chance to emerge. When rumours and misinformation do surface, we quickly counter false stories with verified information and ensure the news stories or posts are removed online. We encourage the people we work for to participate too by sharing verified, trustworthy information within their community.

Lesson 3: Responding to incoming questions, feedback and complaints alone is not enough. Reach out proactively to the most vulnerable households

While actively reaching out to every one of the millions of refugees living in Turkey is practically impossible, Turkish Red Crescent has made thousands of outbound calls, contacting the most vulnerable households. This includes families required not to leave their homes for some weeks due to a mandatory curfew, including anyone over 65 as well as people with disabilities. This proactive approach enabled people to share all their questions and concerns with us, including sensitive issues or requests for additional support.

Depending on the specific needs and concerns raised, Turkish Red Crescent has referred some of these people to other services, such as the national COVID-19 emergency hotline, the social assistance services provided by the Turkish Government, and specialized services from other humanitarian actors, including protection actors.

Conclusion

In Turkey, now more than ever, we must continue to build more meaningful relationships with communities and act on people’s concerns and suggestions. COVID-19 has challenged the way we as a humanitarian sector work, but it has also allowed us to find more innovative solutions to listen to refugees and respond to their needs.

More about the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN)

Home to more than 4 million refugees, Turkey hosts more refugees than any other country in the world. Most of them are Syrians, fleeing a conflict that has been ongoing for nine years. With funding from the European Union, Turkish Red Crescent and IFRC are able to provide monthly cash assistance to the most vulnerable families through the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN). Over 1.7 million refugees benefit from this assistance, enabling them to cover some of their basic needs, including food, rent and utilities, every month.