This blog series will focus on the highlights from different Cash Practitioner Development Programme deployments in 2021, allowing practitioners to share what they have learnt and experienced during their Cash School learning deployments.

The Cash Practitioner Development Programme aims to expand the ready pool of cash experts available to deliver humanitarian cash assistance, and to strengthen the community of qualified practitioners with up-to-date skills in all areas of cash assistance. Cash deployments are a key element of participants learning schedules, these deployments aim to enhance skills and confidence in implementing cash based assistance. Some deployments are run in partnership with NORCAP, with practitioners accessing deployment opportunities from a range of humanitarian agencies.

Name: Ali Eren Karadeniz

Job Title: Cash and Voucher Assistance Officer, Turkish Red Crescent

Where were you deployed?

Remotely deployed to work with Indonesia Cash Working Group

What type of CVA work did you complete as part of the deployment?

During the deployment, I have supported the Indonesia Cash Working Group (CWG) to develop Minimum Expenditure Basket (MEB). In order to facilitate the MEB development process for the CWG, I worked on creating a framework document which the CWG benefitted to shape the discussions on how to calculate the MEB in the best way possible as per their operational needs. This required an intense secondary data review and analysis as well as timely and swift coordination with all members within the CWG.

What was the area you learnt most about?

The areas I learnt most about and grew my skills in were:

- Asia-Pacific region cash coordination structure,

- Overall MEB development process and examples around the world,

- Facilitating decision making in a complex humanitarian environment,

- Remote coordination with humanitarian actors.

What was a ‘stand out’ moment for you on your deployment?

Joining a cash working group for a specific task and for a limited time frame has its own challenges such as developing a mutual understanding between multiple partners and working in close collaboration in a systemized and coordinated way. It was a great feeling when all CWG members agreed upon the geographical scope of the MEB after several discussions and I was quite happy that I could contribute to CWG’s decision making process in a positive way.

Another moment that stood out for me during the deployment was when we, as the CWG, have engaged with the broader humanitarian scheme in Indonesia for their contributions on the MEB. Collecting inputs from different clusters including health, shelter, education etc. have helped the CWG to understand the needs better and make informed decisions about which food and non-food items must be kept within the MEB, which would serve as a baseline for future discussions around assistance amount.

Author: IFRC Cash team

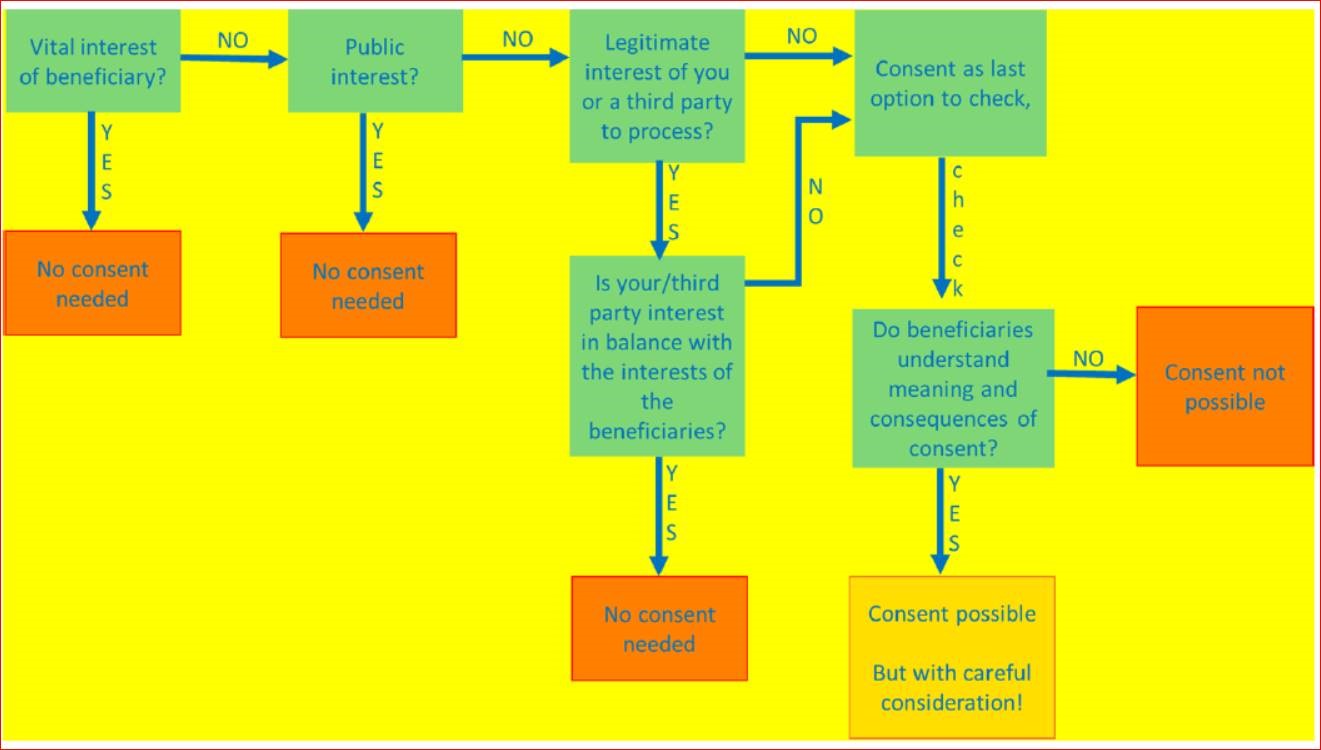

The IFRC has published a practical guidance on Data Protection and Cash and Voucher Assistance (CVA) to help staff and volunteers apply data protection principles in their delivery of humanitarian cash and voucher. The guidance, which complements the Cash in Emergencies Toolkit, lays out the key principles of data protection and carefully guides the reader through the processes of CVA from targeting to post-distribution monitoring, asking a set of critical questions at each stage. Many of the questions are also illustrated by examples and practical advice on how to apply the guidance. The questions include, for example:

- What legitimate basis should I rely on and is consent the most appropriate?

- Do I absolutely need the data collected by an external source and how can I make sure the beneficiary data has been collected in an appropriate manner?

- Is it necessary and safe to share personal data with the donors?

By formulating key questions in an accurate way, the guidance gives practitioners a practical framework for taking decisions in the best interest of the communities they serve.

According to the guidance:

“Data protection is not only a matter of good governance; it is also about building trust.”

Beneficiary trust is, of course, vital for CVA and other humanitarian programmes to succeed. Therefore, by embedding data protection principles into programmes from the outset, practitioners are not only attending to beneficiaries, but also enhancing the reputation of their organisations.

in Cash and Voucher Assistance )

To find out more about this document, watch the recording of this webinar organised to launch the new Practical Guidance for Data Protection in Cash and Voucher Assistance – A supplement to the Cash in Emergencies Toolkit:

Practical Guidance for Data Protection in Cash and Voucher Assistance – A supplement to the Cash in Emergencies Toolkit from Cash Hub on Vimeo.

Find out more:

- Link to CVA Data Protection Guidance: https://cash-hub.org/resource/practical-guidance-for-data-protection-in-cash-and-voucher-assistance-a-supplement-to-the-cash-in-emergencies-toolkit/

- Link to the Cash Hub’s webinar on Cash and Data Protection: https://cash-hub.org/resources/webinar-series/#webinar-18

- Link to webinar introducing the CVA Data Protection guidance: https://cash-hub.org/resource/practical-guidance-for-data-protection-in-cash-and-voucher-assistance-a-supplement-to-the-cash-in-emergencies-toolkit-2/

- Link to CaLP’s webinar: Data simplified. Protection amplified. An essential conversation for CVA practitioners: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLXAi0e320HJwhYFSwpqtL3O0yBPzj-YEU

- Link to ICRC video on Data Protection and Cash Transfer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FfHVagVaK4w&feature=emb_logo

- Link to Digital Dilemmas Dialogue – A Humanitarian look at Assistance Programming and Social Protection Systems: https://www.icrc.org/en/digitharium/digital-dilemmas-dialogue-2

This blog series will focus on the highlights from different Cash Practitioner Development Programme deployments in 2021, allowing practitioners to share what they have learnt and experienced during their Cash School learning deployments.

The Cash Practitioner Development Programme aims to expand the ready pool of cash experts available to deliver humanitarian cash assistance, and to strengthen the community of qualified practitioners with up-to-date skills in all areas of cash assistance. Over the course of one year, participants learning schedules are tailored to their needs and personal experience to date. Cash deployments are a key element of participants learning schedules, these deployments aim to enhance skills and confidence in implementing cash based assistance. Some deployments are run in partnership with NORCAP, with practitioners accessing deployment opportunities from a range of humanitarian agencies. Practitioners can expect to learn experientially through work activities, and to review and evaluate their learning after every deployment.

Name: Nabeh Allaham

Job Title: Cash and Voucher Assistance Coordinator, Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC)

Where were you deployed?

South Sudan, Juba, into the role of Cash Working Group (CWG) co-lead.

What type of CVA work did you complete as part of the deployment?

During this deployment the role of the CWG co-lead in Juba covered a range of tasks, these included: reviewing key documents (Survival Minimum Expenditure Basket, CWG South Sudan Terms of Reference, Cash for Work Guidelines, and South Sudan Humanitarian Fund proposals); supporting the Financial Service Providers, partners and National Society to understand what their main challenges are in the area of CVA; and working on Financial Service Provider mapping.

What was the area you learnt most about?

The areas I learnt most about and grew my skills in were:

- Modalities and Delivery Mechanisms selection

- Partnerships , coordination network

- Development of CVA Terms of Reference

- Cash for Work technical knowledge

- Strategic Directions setting for CWG

- Calculation process of S/MEB.

What was a ‘stand out’ moment for you on your deployment?

There were many key moments from this deployment which stood out. One was the opportunity to be more involved in working with the CWG, getting a better idea about the way in which CWGs work, what are the most important factors that should be considered while supporting and building the capacity of a national and international organization, and understanding the role that CWGs can play in enhancing the coordination and harmonization of the national and international CVA levels.

Other key moments have been: gaining an extensive knowledge of the UN environment system and how much it is different to a National Society; learning that best and important skills that a CWG coordinator should have are being able to keep the network between all the humanitarian actors stable and effective; experiencing how to deal and participate in a new, complicated and complex context with all the stockholders; and learning the role that I have to play in supporting, convening and encouraging CVA parties to participate and help in taking the decisions.

In 2020, the outbreak of COVID-19 in the UK prevented many people from accessing their usual forms of financial support and drove many more into unemployment and severe financial hardship. In line with its mandate, the British Red Cross responded by launching a new emergency cash service: the UK Hardship Fund. The Fund was made possible thanks to a generous donation from a British Red Cross’ partner, Aviva and the Aviva Foundation, with the aim of providing nation-wide, short-term financial assistance to people who are struggling to meet their essential needs.

The Fund offered a tool for British Red Cross and their partner charities to deliver short term direct cash assistance to people, all run through a centralised system at the British Red Cross. Designed for people with complex needs and no income, the Fund offered a one-off payment of £120 or a three-month grant of £360 paid in monthly instalments. As of April 2021, the British Red Cross has distributed £3.1 million in cash grants, supporting 13,016 people.

When you hear feedback, it is easy to appreciate what a difference £120 can make to someone’s life […]. When you have nothing, no income or other form or assistance, this support can make the difference between whether you eat or not in a given day; the fund targets the most vulnerable people who are unable to access any other form of support.

Alex Ballard

Alex Ballard, the Hardship Fund Programme Manager, has offered his thoughts on the most important components of the Hardship Fund: the role of partnerships and the use of technology.

How have partnerships helped the British Red Cross to reach the most vulnerable?

One of the first tasks for the Hardship Fund team was to identify those who most urgently needed financial support: those for whom this Fund represented their only option to meet their needs. This led the team to establish an eligibility criteria that encompassed a no income threshold as well as certain indicators of vulnerability, such as an unstable migration status, deterioration in physical or mental health, or risk of domestic violence. To ensure that they could identify those who met this criteria across the UK, the British Red Cross turned to external organisations who were already working with many of these groups, creating a network of over 300 referral partners.

Thanks to this network of partners, the Fund was able to reach a larger and broader range of people, reflecting the complex and wide-ranging impact of COVID-19 on financial resilience. The aim of the partnership approach was two-fold: to expand the reach of this Fund, and also to ensure that this short-term cash assistance did not stand on its own, and instead complemented longer-term solutions and casework relationships through these engaged partners.

In engaging with partners, the British Red Cross adopted a national approach through regional teams, who were able to build on their local knowledge and existing networks, as well as develop new, exciting partnerships and connections. Alex explains: “we relied on our regional approach to tap into existing local knowledge, which we were able to do well thanks to the long-term presence of BRC teams and the trust that has been built up through volunteers over many years.

The Hardship Fund team showing Bankable Visa cards that will be distributed to deliver cash assistance

By connecting with new partners – local authorities, charities, food banks and community groups – this impact was multiplied, as we were able to connect with wonderful groups deeply involved in their local communities. The long-term value comes from this community connection”.

For future cash programmes, Alex would recommend the partnership approach, but states it could not have been successful without significant time and effort invested into relationship management by regional Hardship Fund leads across the country, who work with partners to support the process and ensure the details of the Fund are explained accurately and uniformly across over 300 organisations.

To steer its vulnerability criteria and partnership approach, one tool used by the British Red Cross is its vulnerability index. This highlights which areas would be expected to have a greater concentration of people in need of support in the UK. The team used this to ensure they were working with organisations in the areas of greatest need, and to ensure a needs-led approach independent of geography.

Data management to scale up assistance during lockdown

Scaling up to safely distribute cash to over 10,000 people, through a process and team that had to work almost entirely remotely, was a unique challenge for the British Red Cross and required the use of secure and adaptable technology.

To do this, the Hardship Fund team collaborated with RedRose, who provided a ready-to-go data management system, and Bankable, who provided regulated cash cards. Thanks to a pre-existing service agreement between RedRose and the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC), the RedRose system was able to be set up rapidly at the start of this response. Alex stresses how, while this technology is often used in less developed contexts, the Hardship Fund showed how RedRose can work everywhere.

Using this technology, the British Red Cross and partners would support somebody to undertake a criteria check and register for the Fund. On successful registration, this person would be sent a cash card, and use a mobile phone to verify with the Hardship Fund team, before cash is remotely uploaded onto the card. If verification is not accurate, an automated support system kicks in. In most cases, sending the card through the post is done on the same day of registration, and the card can be activated electronically, as soon as it has been received and verified. Alex raises the point that:

however clever your system is, there will always be somebody for whom this system doesn’t work. What about someone who doesn’t speak English so well or isn’t comfortable with using text messages? It is important to learn and improve continuously.

Alex Ballard

For this reason, the team established a helpline manned by dedicated staff, and a troubleshooting system. Insights from this and feedback from card users and partners led the team to start offering the instruction letter in 27 languages, to facilitate a smoother process and support a better user experience.

Working with RedRose offered new insights thanks to the data collection opportunities, enabling Information Management experts at the British Red Cross to create dashboards and analyse gaps and trends, steering the development of the programme. Alex explains that these data tools offer a smart overview of quantitative data, that can help us raise the right questions clarifying that these insights can help us challenge our expectations and ensure we are reaching the right people at the right time.

For the Hardship Fund team, the key question for improvement and evaluation has been whether the most vulnerable people have been reached.

We feel that we met the objective of helping even more people that we originally thought we would able to. Given our criteria, anyone we did support was effectively in extreme need of support.

Alex Ballard

Taking referrals from partners stops at the end of June 2021 and although the Hardship Fund will not be continued into the recovery phase, Alex feels that the learning it offers – particularly around about how to work with cash, how to use data and how to harness partnerships – could support stronger, integrated cash services in whatever comes next for cash assistance in the UK.

All feedback received has been incredibly positive and highlighted how the cash allowed people to choose the right assistance for their own needs. The stories we’ve heard from our incredible partners and service users are so inspiring and confirm the impact working together as a sector, using the right technology, and cash assistance can have to support people to prioritise and respond to their own needs at this difficult time.

Alex Ballard

The Baphalali Eswatini Red Cross Society (BERCS) and British Red Cross have published a new case study outlining how BERCS used their experience in cash and voucher assistance (CVA) to influence the Government of Eswatini to adopt mobile cash as the response modality for their humanitarian response and social protection programmes, since the COVID-19 response.

BERCS began advocating about the benefits of CVA in 2016 when they became the first actor in Eswatini to implement cash assistance. The advocacy work was essential to gain the government support needed to pilot a multipurpose cash programme, and throughout the programme transparent communication between BERCS and the government convinced many of the benefits and efficiencies of using CVA. This set a precedent and opened the path for other actors to implement CVA in Eswatini.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Eswatini in March 2020, the Government could not distribute goods in kind in the traditional way. Drawing on the advocacy and experience of BERCS and other actors, the Government implemented the first government funded response using mobile cash.

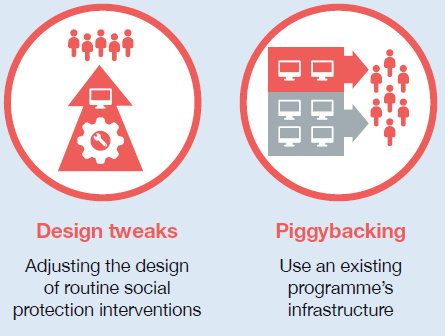

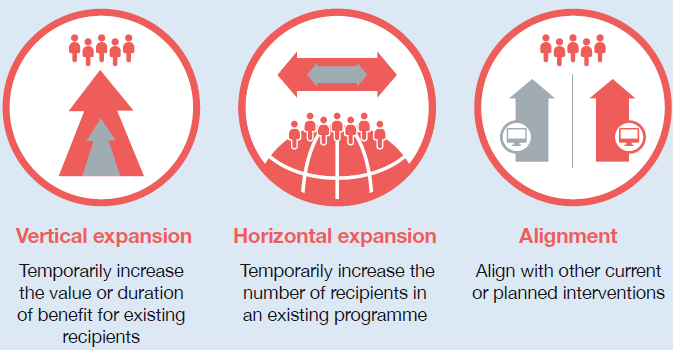

BERCS was actively consulted and used its experience to inform the response plan. The response was a success, covering 25% of the population with 91% of recipients confirming they were happy with the support.In line with this success, the Government of Eswatini also switched the modality of existing social assistance programmes from cash in envelopes to mobile money. This is known as a ‘tweak’ to the social protection system. This is a practical example of how BERCS’ advocacy efforts resulted in a more efficient and streamlined delivery mechanism for social assistance.

BERCS continues to work closely with the government and there are opportunities to further strengthen the links between humanitarian response and social assistance. Globally, National Societies are well-positioned to use their auxiliary role and expertise to advocate for wider use of CVA as one step to strengthen social protection systems, which can be adapted in different ways to better support those in need.

For more information about the experience in Eswatini and the unique role that National Societies can play to improve social protection mechanisms, download the full case study here.

The Cash and Social Protection page also offers access to many different resources explaining what social protection is and how National Societies can engage in this area.

The Zambia Red Cross Society (ZRCS) has been assisting affected population in Zambia through the IFRC global Emergency Appeal for the COVID-19 pandemic. Among its response options, ZRCS has provided cash support to the affected households whose members had lost their income or were at risk of adopting negative coping mechanisms to meet urgent needs in the context of the global pandemic.

During the month of November 2020, ZRCS registered 1,303 households and carried out the verification and validation of those in Chililabombwe and Kalulushi districts. Each family received ZMW 410 per month for a period of 6 months. This assistance was provided in two instalments, with each instalment covering amounting ZMW 1,230 for 3 months. The first instalment was disbursed during November 2020 while second and last tranche took place during March 2021.

ZRCS is part of the National Cash Working Group (NCWG) chaired by the Ministry of Community Development and Social welfare. The NCWG includes different organisations implementing cash assistance in Zambia. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, the NCWG held numerous meetings to harmonise COVID-19 emergency cash response for all partners in the country, to avoid duplication of efforts and also to ensure the partners are supporting the social protection efforts of the Government. The Chililabombwe and Kalulushi districts in the Central Province were assigned to ZRCS as its area of implementation to distribute cash assistance.

The most vulnerable families already registered for government social cash transfers and have been prioritised. The ZRCS applied vulnerability criteria to select the most vulnerable among the registered population. Each selected household was expected to meet at least one of the vulnerable eligibility criteria, such as:

- Elderly with 65 years of age and above;

- Female headed household;

- Child headed household;

- Households with chronically ill member/s;

- Households with differently abled people.

To find out more watch a short video on the “Zambia Red Cross Emergency Cash Transfer Response” clicking here.

Author: Zambia Red Cross Society

In Zimbabwe, the “Resilience through Disaster Response management; Multipurpose Cash Preparedness and Comprehensive School Safety Project” has concluded in 2020, after running for two years in collaboration with Finnish Red Cross (FRC), European Commission Humanitarian Aid Office (ECHO), UN World Food Programme (WFP) and British Red Cross (BRC) – with the main implementation being led by Zimbabwe Red Cross Society (ZRCS).

The first project objective was to increase the capacity of ZRCS staff and volunteers to plan and implement cash and voucher assistance (CVA) programmes to run effectively. The information and tools to increase knowledge and skills of those involved in delivering CVA were based on the Cash in Emergencies Toolkit developed by the Movement, as well as inputs by WFP.

ZRCS is in the process of successfully mainstreaming CVA, as shown by the use of CVA in the 2020 contingency plans in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. Its integration has also been included into plans for 2021-2023, and into the Standard Operation Procedure which is currently being finalised to ensure the COVID-19 adaptations and the IFRC 2030 strategic plans are fully considered.

An overview of the crisis

Zimbabwe is affected by food insecurity across the majority of the country due to drought and flooding which have led to 5.5 million people (59%) of the rural population facing food insecurity. People have also experienced a worsening economic crisis. As part of efforts to address lack of foreign investment and lack of USD cash, the government has introduced a range of policies in recent years.

Despite these policies, inflation has continued unabated, with inflation rate growing exponentially in 2019, and reducing the purchasing power of households with already depleted food stocks.

How did ZRCS prepare to deliver CVA?

Continuing to learn about the use of CVA remains a focus of the work of ZRCS, whose staff and volunteers received training both online and in person. A finance and logistics workshop also took place with a key focus on Financial Service Providers (FSPs) with participants from different provinces and from the headquarter, coming from finance, logistics and admin backgrounds.

Cash Simulation Exercise – Nov 2020

The partnership with WFP allowed to extend training to include information management and the use of SCOPE; a beneficiary and transfer management platform that supports the WFP programme intervention cycle. This project has enabled a productive relation between ZRCS and WFP. The partnership was established and evolved into a strong collaboration with ZRCS as the implementing partner in the Lean Season Assistance operations in 2019/2020. Additionally, a number of joint activities and training have also strengthened the delivery capacity of ZRCS.

What were the lessons learned?

Distributing CVA has faced a wide range of challenges, including a change around currency across the country, together with the sudden creation of new rules on the use of mobile money. Due to this the team had to adapt the modality used to distribute cash assistance different times, moving from physical cash in envelops to mobile money to vouchers. The preferred modality sometimes varied also from region to region, and from one month to the next, giving staff and volunteers an opportunity to show their capacity to be versatile.

Having a good connection to the communities helped make these transitions easier. Through this process the ZRCS had a chance to reflect on the importance of cash and voucher assistance for the community, whose feedback was recorded in different ways.

Using cash transfers increases flexibility, dignity of beneficiaries and it gives them a choice to make […] as the communities have different priorities. Some people need money for medication, some need money for food, some for school fees, so having cash makes all these options possible. This is why at the ZRCS we are proud of using cash and voucher assistance.

ZRCS staff member, 2019

This process also led ZRCS to strengthen its commitment to community engagement and accountability (CEA) and to organise a joint learning event with the Kenya Red Cross Society as well as a CEA workshop.

Standard Operating Procedures Review – Oct 2020

To ensure the use of CEA was going to become an integral part of the work of the ZRCS, duties related to CEA have been added into job descriptions and training has been provided to volunteers. ZRCS has also recruited a CEA officer to ensure that staff continues to engage the community and to be accountable to them when implementing the programmes designed to reflect their preferences. In this way, CEA has emerged as a key element to ensure the best choices are made to achieve the desired objectives when distributing CVA.

Extract from the ICRC, Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog channel, for the original blog, to access a short podcast on this topic or to read comments to the original blog click here.

By: Pierrick Devidal

“Cash has been an exceptional vector of progress in humanitarian action, empowering people, protecting dignity, mitigating the negative secondary effects of in-kind assistance, improving accountability to affected populations, increasing participation in humanitarian and development responses, supporting local economies and, last but not least, boosting operational efficiency, which in turn saves some humanitarian cash. But what happens when cash goes digital, bringing with it the risks of exclusion, discrimination, or surveillance? In this post, ICRC Policy Advisor Pierrick Devidal opens an honest conversation as to whether and how humanitarians should continue using digital cash.

‘Cash’ is no longer a dirty word in the humanitarian sector. Over the last two decades, it has evolved – from a synonym for operational agility, to a relatively niche innovative humanitarian approach, and now to a global standard of good humanitarian assistance practice. People love it, humanitarians love it, and donors love it. It is reasonable to say that its weaknesses are largely compensated by the benefits it brings. Cash is a humanitarian no brainer.

And maybe that’s the problem.

Because cash is no longer cash. It is dematerialized and digitalized. It is all forms of digital payments including prepaid cards, electronic vouchers, and cryptocurrencies – and it has your name on it. Unlike real physical cash, digital payments are linked to identities and personal information. As a result, they can identify, they can exclude, and they can discriminate. Yet, falling in line with the global digital transformation, humanitarian programmes using cash transfers have turned, en masse, to digital solutions.

There are logical reasons to consider digital cash a good solution – if cash has been shown to enhance autonomy and resilience, and the world is going digital, why should people affected by conflict be denied access to something most of us use on a daily basis?

In parallel, the dark side of digital solutions is emerging and the over-enthusiastic and relatively naïve fascination bias for digital technologies is passé. The infodemic, massive cyber-attacks, data protection scandals and ‘surveillance capitalism’ are shining a light on the paradox of progress and the dark side of digital technologies, calling for a more sober approach. It seems that the humanitarian sector is also starting to realize that, maybe, digital solutions are not always a no brainer.

And maybe that is a good thing.

As recent articles have highlighted, there may be a case against digital cash. While the cashless cash trend is accelerating under the influence of economic actors, donors and the COVID-19 pandemic, critics are pointing to the increasing risks of ‘data colonialism’, ‘surveillance humanitarianism’, ‘techno-solutionism’, ‘data injustice’ or ‘digital exclusion’. What cash can do, digital cash can do in reverse. The critics raise uncomfortable but important questions for the humanitarian sector.

In short, it seems that humanitarians are finally taking a deep breath and a step back from the race to adjust to the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ and realizing that in contexts where violence and persecutions are widespread, we need to talk about digital solutions and cashless cash.

Cashless cash vs. principled humanitarian action

There are many entry points and angles to this conversation. Some of them more obvious than others. There are technical dimensions that are related to operational considerations, risk management or data protection questions. There are strategic dimensions that are related to questions of positioning, competition and relevance. And there are political and ethical dimensions. It is a multilayered humanitarian puzzle.

Digital payments may create significant interference with the fundamental humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence, commonly referred to as NIIHA. It is however not clear yet whether, and how much, these tensions are manageable.

Digital technologies, including digital payment mechanisms, are not neutral. They are aligned with the political objectives of those who create and promote them, including tech companies, banks and governments. In countries affected by armed conflict or other situations of violence, these actors are – to put it mildly – not always neutral. Being associated with them or their objectives can raise perception issues and put the neutrality of the humanitarian actors who use them into question (and ultimately, jeopardize their security).

Because digital payments are often carried out in partnership with financial service providers that have significant control over the parameters of digital payments, including flows of personal and sometimes sensitive data, the operational independence of the humanitarian organizations who use them can become compromised.

Those same financial service providers operate under different legal frameworks and have a different mandate (i.e. profit), so partnering with them may create tensions with the ability of humanitarian organizations to operate and deliver with impartiality – based on needs only – and not on needs and, for instance, States’ security considerations.

Finally, by replacing the human element by a digital interface, some are concerned that we are sacrificing some crucial components of humanity.

Cashless cash and ‘do no harm’

The ‘do no harm’ principle is sacrosanct in the humanitarian sector – or rather, humanitarian actors always try to do as little harm as possible, by mitigating the negative impact that their interventions and activities may bring for the affected populations they serve, and to the environments in which they operate. But with digital payments becoming the standard, there is a feeling that humanitarian organizations really have no choice but to adopt them.

That pressure trickles down. Even when we may be able to identify some of the risks attached to digital payments, and without necessarily having the solutions yet to mitigate those risks effectively, we offer digital payment solutions to affected populations, and we don’t always offer them an alternative, particularly given that some say we live in a post-consent world. Do recipients really have a choice? Are we not transferring risks and this lack of choice to them; or, if we collectively decide to stop using digital payments, are we taking away power and making a paternalizing choice for affected populations?

These are not easy questions, and there are even bigger ones. Is it realistic or ethical to pause digital payments in humanitarian programmes? Can we really afford the human and financial cost of forgoing proven lifesaving assistance or of reverting to in-kind, which can be less effective? Do we need more regulation, or a plan B?

These are existential questions, because they relate to trust in humanitarian action. And the new oil is not data; it is trust. We invite our fellow humanitarians, States, the private sector and, most importantly, affected people, to join us in the conversation.

Extract from the ICRC, Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog channel, for the original blog, to access a short podcast on this topic or to read comments to the original blog click here.

By: Pierrick Devidal

An updated version of the Household Economic Security (HES) guidelines has recently been launched by British Red Cross. To download this document, the analytical overview and the HES glossary click on the links below:

- Household Economic Security (HES) guidelines – step by step guidance

- HES Analytical Overview – providing a list of driving analytical questions for a HES assessment

- Key HES Terminology – providing an updated glossary to help unpack the 3 components of HES and related concepts

The guidelines and all its supporting documents, including tools for data collection, a HES report template and example reports in multiple languages can also be found on the IFRC Livelihoods Centre Website.

The HES guidelines are based on the Household Economy Analysis methodology and can now be applied to both rapid and slow onset emergencies, and also used to gather baseline information for livelihoods and resilience building interventions.

Breaking down Household Economic Security into 3 components (food security, basic needs and sustainable livelihoods) can help colleagues of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement navigate the humanitarian and development landscape as part of their operational reality and mandate. The guidelines may also be useful for other actors involved in food security, economic security and basic needs and livelihoods assessments.

Ömer Eddağavi and his family have been living on unstable income since arriving in Turkey six years ago after fleeing conflict in Syria.

Relying on seasonal work on farms, forced Eddağavi to borrow money from relatives and friends when there was no job to feed his family.

“It is so hard to be dependent on debts when you are responsible for a crowded family. Because you don’t know if you will be able to borrow money next time,” said Eddağavi.

However, since the day they started to receive the monthly cash assistance offered by the IFRC and the Turkish Red Crescent, with funding from the European Union, Eddağavi and his family broke the vicious cycle of debt to stay afloat.

“Thanks to god, we can live without being in debt and pay our bills,” said Eddağavi.

More about the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN)

Funded by the European Union’s Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), IFRC and Turkish Red Crescent are providing monthly cash assistance via debit cards to the most vulnerable refugees in Turkey under the ESSN programme. This is the largest humanitarian programme in the history of the EU and the largest programme ever implemented by the IFRC.

ESSN is providing cash to the most vulnerable refugee families living in Turkey. Every month, they receive 120 Turkish Lira (18 euros), enabling them to decide for themselves how to cover essential needs like rent, transport, bills, food, and medicine.

*This story was originally published on Turkish Red Crescent’s kizilaykart.org website and adapted by the IFRC.

This article covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.